Commentary on nature, visual and performing art, travel, politics, movies, and personal ideas

Friday, June 3, 2016

BOOK REVIEW: The Door, by Magda Szabo; or Good Help is Hard to Find

This book was highly praised by The New York Review of Books. I didn't twinge at the narrative summary - a woman who becomes involved in the life of her housekeeper, but I should have.

Spoiler: My opinion is that of a privileged American woman with littler tolerance for muddled unreasonable individuals.

A narcissistic writer who becomes a literary success needs help managing her household because she doesn't have time to write. Her husband is an oblivious paleolithic male who doesn't seem to think he needs to help her. She doesn't think there's anything wrong with this picture.

She hires a highly recommended housekeeper but allows her to set her own hours, and choose her own tasks and menus. Personal boundaries break down between the woman and her housekeeper and she quickly becomes an obnoxious tyrant. The writer allows herself to be trampled by cruel judgments, harsh criticisms, and outrageous relations, I guess because she's spoiled by the high quality service and food (when she gets it), and feels guilty because of class distinctions.

The writer discovers how tragic events damaged her good and faithful servant; the Holocaust and the Hungarian uprising make grievous wounds. Housekeeper has made her victimhood into self-tyranny and primitive obdurance, inflicted upon everyone else.

In the end, the housekeeper's own home is dirty and hoarded full of junk, and whatever valuable furniture she was going to receive from the housekeeper is found to be full of worms and worth nothing.

The keeper from this: some people construct unassailable protected defense mechanisms that are so filled with anger they can't be saved. Even protecting them from themselves is impossible. So this is news? To whom?

PAINTING: Agnes Martin, LACMA

Oh, dear. Sometimes I think I love the philosophy, intentions, and writings of Minimalist abstract expressionists more than I love the actual artworks.

That said, I love Agnes Martin's work - all of it. She seems to be to be the perfect pure artist, refined, filled with joyful and kind intention and attention, empty of self, transcended and suspended in the moment, in the world yet fully in spirit, a true vector for glimpsing the Tao, and accepting the self and its limits, as Freud concluded we must.

Looking at her work is like always being able to hear the distant and poignant whistle of the train.

In this photo, so stoic, present, and resolved, gazing with full knowingness, and the quality of borne pain it carries - Agnes Martin reminds me so much of photographs of my grandparents and great-grandparents from the late 1800's and early 1900's - German farmers tough of spirit, dour, and almost sullen as the face the camera. Of course, they didn't smile because they had to hold still for so long to expose the film, right?

So what and who does she make me yearn for? For Martin Avery, for Mark Rothko, for Sean Scully.

That said, I love Agnes Martin's work - all of it. She seems to be to be the perfect pure artist, refined, filled with joyful and kind intention and attention, empty of self, transcended and suspended in the moment, in the world yet fully in spirit, a true vector for glimpsing the Tao, and accepting the self and its limits, as Freud concluded we must.

Looking at her work is like always being able to hear the distant and poignant whistle of the train.

In this photo, so stoic, present, and resolved, gazing with full knowingness, and the quality of borne pain it carries - Agnes Martin reminds me so much of photographs of my grandparents and great-grandparents from the late 1800's and early 1900's - German farmers tough of spirit, dour, and almost sullen as the face the camera. Of course, they didn't smile because they had to hold still for so long to expose the film, right?

So what and who does she make me yearn for? For Martin Avery, for Mark Rothko, for Sean Scully.

|

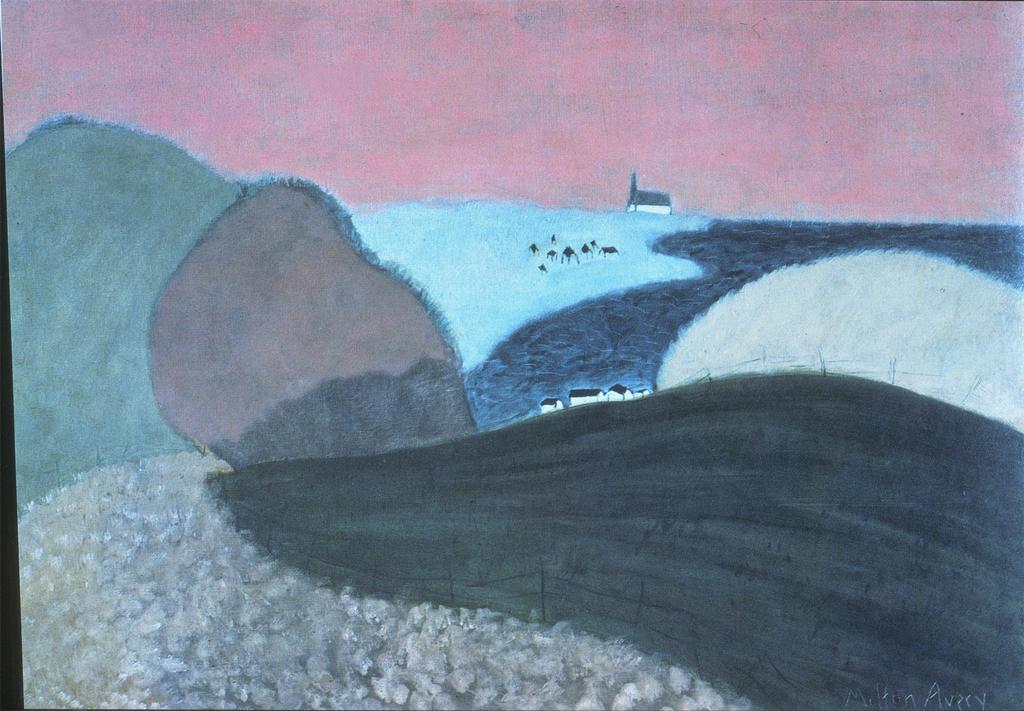

| Midwinter, 1954 |

|

| Untitled, 1959 |

|

| Untitled, 1960 |

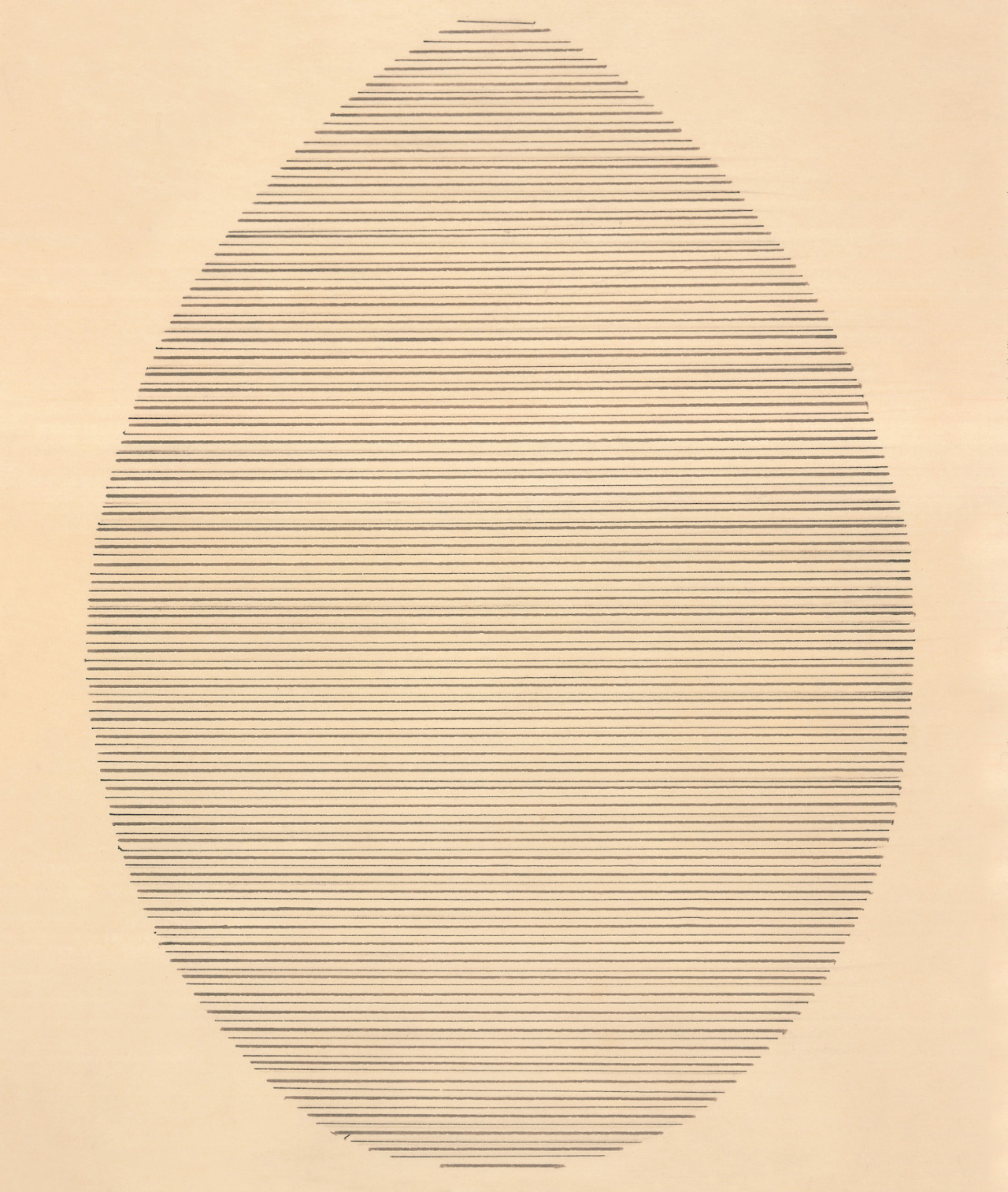

No one talks or writes much about whether Martin's diagnosed schizophrenia shaped her art, how, and how much. As I look at the body of work, I think I feel the grid as a cage, a prison always settled over her being in which she worked ceaselessly with as much precision as she could bring to bear to explore the possibilities of her constrained existence.

Of course, that's what we've all got, right? The ultimate non-knowing subjective state of what we can know and not know we don't know; the physical constraints of perception, the body and time which construct that grid..

Of course, that's what we've all got, right? The ultimate non-knowing subjective state of what we can know and not know we don't know; the physical constraints of perception, the body and time which construct that grid..

How satisfying, now beautiful, how right.

|

| Friendship, 1963 paper |

|

| The Egg, 1963 ink on paper |

|

| Untitled, 1995 oil on canvas, 6"x6' |

|

| Mark Rothko |

|

| Sean Scully, Home |

ART: Grazing the Internet, Edward Kienholz, Rachel Whiteread

Rachel Whiteread's artwork, "Cabin", is being installed on Governor's Island in New York City. It's a reverse concrete cast of a small outlying building. Looks so marvelous with the sophisticated architecture behind it, a ghost-dwelling for those who seek America first spiritually and then in body.

|

| 5 Car Stud, 1969-1972, Edward Kienzholz |

The effect Kienholz' installations had on me when I was in my 40's was ultimately political, didactic, pandemic agreement. I was an art equivalent of a demagogue - familiar refrain these day, yes? - ranting at injustice. Look, see what misery, horror, loneliness, suffering, injustice really looks like? Stop it now! Make it stop!

In my 70's now, it seems that a much less egotistical narcissistic reaction occurs. It's quiet, grieving: a perspective sees that the earth constricted in spatial and temporal bands of suffering and injustice that can never be forgotten - not one death redeemed, all lost. It must be pushed until death, another level of Sisiphys-ian existence.

PAINTING: Emily Carr, seminal Canadian ethnographer and painter

I can hear the

Rhine Maidens'

far-away echo,

grieving the

inevitable rape

of our earthly

home.

I learned about Emily Carr when I was exploring the Canadian landscape painters called "The Group of Seven".

She documented the Native American tribal cultures of Canada, frequently painting their totems and other craftwork. A current exhibit at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria documents her life, work, and influence on the next generation of artists.

Steve Martin recently curated an exhibition at the Hammer on Lawren Harris, which focussed attention on this fascinating art group. Their work is dynamic, lyrical, celebratory; images of American landscape unplundered, unspoiled by fracking and gas pipelines.

|

| secret fracking dumping operation disposing of waste fluids in Canada |

The Group of Seven, also known as the Algonquin School, was a group of Canadian landscape painters from 1920 to 1933, originally consisting of Franklin Carmichael (1890–1945), Lawren Harris(1885–1970), A. Y. Jackson (1882–1974), Frank Johnston (1888–1949), Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), J. E. H. MacDonald (1873–1932), and Frederick Varley (1881–1969). Later, A. J. Casson (1898–1992) was invited to join in 1926; Edwin Holgate (1892–1977) became a member in 1930; and LeMoine FitzGerald (1890–1956) joined in 1932.

Two artists commonly associated with the group are Tom Thomson (1877–1917) and Emily Carr(1871–1945). Although he died before its official formation, Thomson had a significant influence on the group. In his essay "The Story of the Group of Seven", Harris wrote that Thomson was "a part of the movement before we pinned a label on it"; Thomson's paintings The West Wind and The Jack Pine are two of the group's most iconic pieces.[1] Emily Carr was also closely associated with the Group of Seven, though was never an official member.

Believing that a distinct Canadian art could be developed through direct contact with nature,[2] the Group of Seven is best known for its paintings inspired by the Canadian landscape, and initiated the first major Canadian national art movement.[3] The Group was succeeded by the Canadian Group of Painters in the 1933, which included members from the Beaver Hall Group who had a history of showing with the Group of Seven internationally.[4][5] (from Wikipedia).

Another artist I include in this genre is Rockwell Kent, an unusual

illustrator and painter who lived in Alaska and Greenland,

an Ayn Rand caricature well known for marvelous illustrations for an

edition of "Moby Dick". His work is reductive, frozen,

filled with germanic, gothic Wagnerian grandeur.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)